Soo Yong and William Boyd in a still from the film ‘The Secret of the Wastelands’ (1941). (Paramount Pictures) Gao Yunxiang, Toronto Metropolitan University

Soo Yong and William Boyd in a still from the film ‘The Secret of the Wastelands’ (1941). (Paramount Pictures) Gao Yunxiang, Toronto Metropolitan University

The recent Netflix series Hollywood creates a make-believe 1948 ceremony in which the noted Chinese American actress Anna May Wong wins an Oscar. In reality, an Oscar eluded Wong during her four-decade film career. Wong, who was born in Los Angeles in 1903, was famously passed over for the lead role of O-lan in the 1937 classic hit, The Good Earth. Instead, Austrian-born white actress Luise Rainer was cast — and for her work, won her second Oscar for best actress. Hollywood’s Motion Picture Production Code (known informally as “the Hays Code”) explicitly forbade depiction of screen intimacy between people of different races. Wong was reportedly heart-broken about the decison.

Anna May Wong, 1932 portrait by Carl Van Vechten. (Carl Van Vechten/Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons)

The desire to posthumously grant Wong recognition as seen in the series Hollywood should also alert audiences to the significant contributions of the other actors of Asian descent who appeared in The Good Earth. One of those actors was Soo Yong. Yong had campaigned for the lead role but she was also passed over. Yong eventually accepted two supporting roles in the movie, one of the most influential Hollywood films on China. Yong’s journey to Hollywood and the way her career contrasted Wong’s reveals much about Hollywood’s racist casting decisions and the racial barriers faced by Chinese American actresses. Yong’s career also reflects the dynamic and shifting development of 20th-century Chinese-American relationships: When contrasted with Wong, Yong’s calculated path towards a “respectable woman” reveals much about how both American Hollywood and Chinese popular culture wanted to depict Chinese women.

Alternative to familiar stereotypes

Yong’s profile aligned with the concept of the Chinese New Woman promoted by the Chinese Nationalist government that emphasized education, chastity and patriotism. Yong strove to present a dignified and educated Chinese womanhood on screen and stage, an alternative to the familiar binary stereotypes of the subservient China doll and the vicious dragon lady. She showcased an aristocratic and intellectual style of sophistication and glamour, void of over-sexualization. Hollywood filmmakers were entranced by her talents and assured by favourable Chinese attitudes toward her as China was a significant market.

Circle of Chinese intellectuals

Born in Hawaii to Chinese immigrant parents in about 1903, Yong was orphaned as a child, and largely raised by her sister, Harriet, who was later a force in Hawaiian politics. After graduating from the University of Hawaii, Yong ventured to mainland United States in 1926 to earn her master’s degree at Teachers College, at Columbia University. She was one of 50 women of Chinese descent in American colleges at that time, and one of the very few in graduate programs, who became recognizable figures in China’s intellectual life. Yong was a student of noted educator John Dewey. She grew close to other students who also studied with him, including Zhang Pengchun, a distinguished dramatist and professor from Nankai University, and Chih Meng, the future director of the China Institute in New York City. Yong became involved in the transpacific modern drama movement initiated by Zhang and Meng. After starring in plays written by Zhang, she began an acting career with bit parts in Broadway productions.

Yong on Broadway and in Hollywood

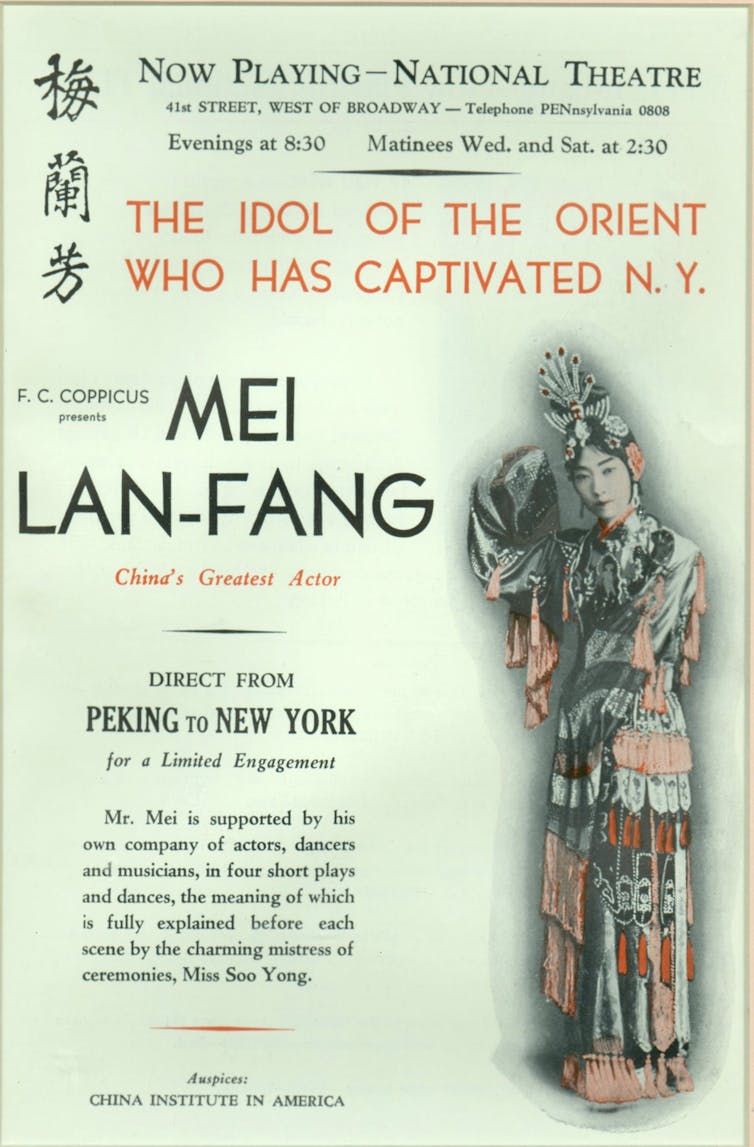

Yong’s big break came in 1930 when she was hired to interpret the performances of Mei Lanfang, the famous Chinese theatrical personality, sponsored by the China Institute. Yong enrolled in a doctoral program at the University of Southern California between 1933 and 1936. She said her ambition was to be a great actress with a PhD. In the eyes of the public, her desire for advanced education helped to distinguish her from Chinese immigrants. It also positioned her as an equal to elite Chinese and American intellectuals.

Photo showing Soo Yong and Clark Gable in a still from the film ‘China Seas.’ Yong autographed it to ‘The Young Companion Pictorial,’ in November 1935, a popular magazine in the Republic of China. (Yunxiang Gao)

Photo showing Soo Yong and Clark Gable in a still from the film ‘China Seas.’ Yong autographed it to ‘The Young Companion Pictorial,’ in November 1935, a popular magazine in the Republic of China. (Yunxiang Gao)

Hollywood casting agents chose Soo Yong for visible roles in films produced by major studios, starring Hollywood icons like Clark Gable, Greta Garbo, Mae West, Gary Cooper, John Wayne and Marlon Brando. Despite her generally limited screen time, Yong frequently occupied within the first 10 spots on billing — the list of names at the bottom of an official poster — which testified to her respectability, popularity and great negotiation skills. She worked up to the highest level of Hollywood stardom allowed for a non-white actress.

Chinese ‘New Woman’

The highly influential 1943 visit to the United States by Madam Chiang Kai-shek, the American-educated first lady of the Republic of China, dominated the contentious process of representing Chinese womanhood. Yong embodied Madam Chiang’s brand of glamour, defined by jewellery, high fashion, perfect English, advanced education, sophistication and a happy marriage. In 1939, The Chinese Digest, the leading English-language Chinese publication in the United States, said Yong belonged to “Madame Chiang’s school” of women. In 1941, Yong married C.K. Huang (黄春谷), a businessman who lived in Winter Park, Fla., after changes in immigration law enabled her to marry a Chinese citizen without losing her U.S. citizenship. With Huang, Yong ran the Jade Lantern, a successful Chinese novelty shop. Customers shopped there for a lifestyle associated with her glamour and were served by the star they recognized.

White Hollywood smitten

White Hollywood was smitten by Yong. She developed an educated, middle-class persona that contrasted with how Hollywood cast Wong. Unlike Wong, who often had to display bare skin and perform sexualized roles, Yong was always fully clothed and displayed sophisticated glamour in her roles. And unlike Wong, Yong never played parts that involved physical abuse or death. Wong’s film persona, created for her by racist Hollywood casting decisions, irritated China’s Nationalist government. Yong’s screen roles presented a softer orientalism that allowed ethnic dignity and did not offend her Chinese American audience or her nationalist friends in China. The Huangs visited China in 1948, recording two rare Cantonese operas while there (released on Folkways Records in 1960 and 1962). The Huangs lived in Winter Park until 1961, when they returned to Hawaii. That year, they were awarded the Rollins College Decoration of Honor for their community contributions. After a series of smaller roles in 1950s Hollywood classics including Sayonara, Yong made a cameo in the 1961 film Flower Drum Song, a Hollywood milestone with a largely Asian cast. Yong secured small parts in four episodes of Hawaii Five-O between 1971 and 1978, in which her husband also appeared. She also appeared in two episodes on Magnum P.I. in 1981 when she was 78. Huang died in 1980; Yong passed away in 1984. The couple’s estate established scholarship funds at the University of Hawaii and at Rollins College. Yong rejected western racist attitudes that associated being Chinese with ignorance and servitude and instead showed a cosmopolitan “Chinese woman at her best.” This is an updated version of a story originally published on April 25. It clarifies the preferred order of names for Zhang Pengchun in the customary Chinese way.![]() Gao Yunxiang, Professor, Department of History, Toronto Metropolitan University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Gao Yunxiang, Professor, Department of History, Toronto Metropolitan University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.